Why Has The Old Pebble Beach Become So Alluring?

Over 25 years since the evolution of the storied course has become understood, worldwide yearning for the old look speaks to the power of naturalness, imagery and shifting tastes.

Most Crosby/AT&T traditions have vanished. The celebs, pro jocks, and CEO’s have been reduced to 36-holes and were almost treated as annoyances during round one’s broadcast (unless they had a famous caddie). In just a few years, viewers have gone from suffering through a name-dropfest to asking, “is that who I think it is and why aren’t they mentioning that he’s playing with this anonymous pro we’re interviewing like he’s a Nobel laureate?”

However, players run the show these days, and they have shown total disdain for the old format or the setting’s role in building the PGA Tour. They don’t have time for perspective. But at least the big wigs will have their wheels up before some Grade A Der Bingle-approved weather arrives.

While the Saturday pro-am antics and celebrity juice may be gone, a new tradition has become part of tournaments at Pebble Beach Golf Links. My apologies in advance, but I’m going to immodestly take credit for helping start an annual debate about the old Pebble Beach look. (I hereby submit Exhibit A, 1999’s The Golden Age of Golf Design.)

In the twenty-five years since that book of vintage photos was released, I’ve continued to push the case for old Pebble’s beauty and brilliance on my blog, in this newsletter, in magazine stories, and even on the Golf Channel, where we considered the complexities involved in restoring more of the old look. This feature aired prior to the 2019 U.S. Open:

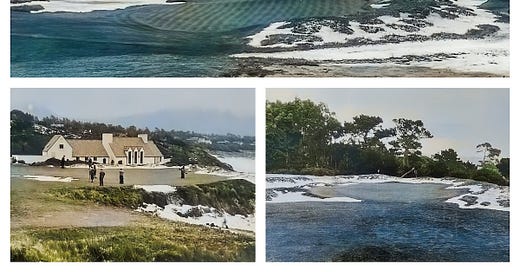

As the photos and course evolution have become better understood, Pebble Beach has begun to reclaim green space on several holes (6, 8, 13, 14, 17, most notably). Much of the work still fails to reclaim valuable hole locations and other subtleties found on a classic course. (At least the early week footage in 2025 suggests a revamped sixth green looks infinitely better, at least when seen from a sensational crane view shot.)

This week, the USGA posted a question to followers about the old look on their social accounts. And like other posts in recent years on Pebble Beach’s official accounts, the persistence of the restoration question says a lot about how much interest exists in courses, different design approaches, and the potential for creating wild, uber-natural golf.

The responses are always lively and largely in favor of returning elements of the old look, interspersed with the usual smattering of naysayers suggesting how unfair it looks or how the peninsula’s weather would make maintenance of the dunesy landscape next to impossible. But most of the commenters are enamored with the audacity of the old par-three seventh and its intricate putting surface shape when juxtaposed with today’s nearly circular green (caused by years of wear, tear, mowing, and a substandard early 1990’s rebuild).

Some confusion over Pebble Beach’s architects involves a basic misunderstanding of how the design reached its 1929 zenith. Over the years, and after I presented all of the evidence of Pebble Beach’s evolution in Golden Age, various rankings and other listings have continued to misunderstand the role of H. Chandler Egan. If he’s mentioned at all.

Why overlook the man? He was reportedly a nice fellow and a great American story: Ivy Leaguer, Olympic medalist, and epic golfer who designed sensational courses. Perhaps his name is still left out because it doesn’t fit on a listing?

In official resort materials, the Pebble Beach Company has long skirted mentions of Egan until recent years, where he’s at least viewed as a contributor. But it underestimates his impact. And I get that it’s easy to become enamored with the idea of two amateurs having somehow created a masterpiece only to never to do it again. Some type of one-hit wonder euphoria.

AI also has a ways to go, but at least Google has a mostly accurate description, while ChatGTP has a lot more training to do. It's weird how $18 billion just doesn’t buy what it used to.

None of the credit stuff should matter.

The 1919-1926 course struggles resulting from Neville and Grant’s work have been well-documented in Neil Hotelling’s Pebble Beach books, which also pay tribute to their shrewd routing (along with the evidence that architect Herbert Fowler made the 18th into a par 5). Still, Pebble Beach’s evolution features a progression worth recapping: