Part 2: Furrow Furor

The 1953 and 1962 U.S. Open's at Oakmont produced more drama over bunker maintenance practices.

Undeterred by Bobby Jones and 1935’s gripes about the bunker maintenance practices, Oakmont continued furrowing their dark Alleghany river sand with “dragon’s teeth rakes.” When Hogan, Snead, and friends showed up for the 1953 U.S. Open, neither Henry or William Fownes was around. Yet, extreme setup measures were so ingrained in the club ethos that players were on edge in the months leading up to the June event. The USGA appeared to be caught between players and the club. Here’s how the furrowing furor went over before the Oakmont’s next two championships.

The 1953 U.S. Open

Even with rain turning Oakmont easier during the 1951 PGA Championship—a golfer dared to break 70!—select players threatened a boycott ahead of the 1953 U.S. Open. Not helping their mood: the championship’s format at that time.

Everyone but defending champion Julius Boros would play two qualifying rounds with no day off before the U.S. Open started. Even three-time champion Ben Hogan had to qualify. All the while, there as a behind-the-scenes push to prevent the club from maintaining its bunker furrowing tradition and the tussled remained unresolved up to the weekend before. The cries were exposed by columnist Chester Smith.

“For the country's professional golfers to even so much as hint of a boycott of the National Open next month unless the United States Golf Assn. and the Oakmont club agree not to furrow the traps is in extremely bad taste,” Smith wrote in the Pittsburgh Press. “For the pros to actually go through with any such action would do damage to their cause that might take years to repair.”

Even with the 1950 passing of William Fownes, the club wanted to furrow the bunkers. Smith reminded everyone of Fownes’ infamous stance:

“Let the clumsy, the spineless the alibi artist stand aside,” Fownes wrote. “When you are selecting the Open champion of the United States, the most prized golfing title in the world, why not get the highest premium on this title?”

Smith shared the player gripes leftover from the previous Open and PGA, citing concerns centered around “the roughening of the sand in the bunkers, the speed of the greens and the positions where the holes were cut.”

Otherwise, they absolutely adored the previous Oakmont setups.

“This is not the first time the money mob has taken out after Oakmont,” Smith wrote of the pros. “They began swinging their verbal mashles at the course on the Hulton highlands long before the last putt went down in the 1935 Open, the last held on that course, and they kept it up for months.”

Don’t forget 1927, too!

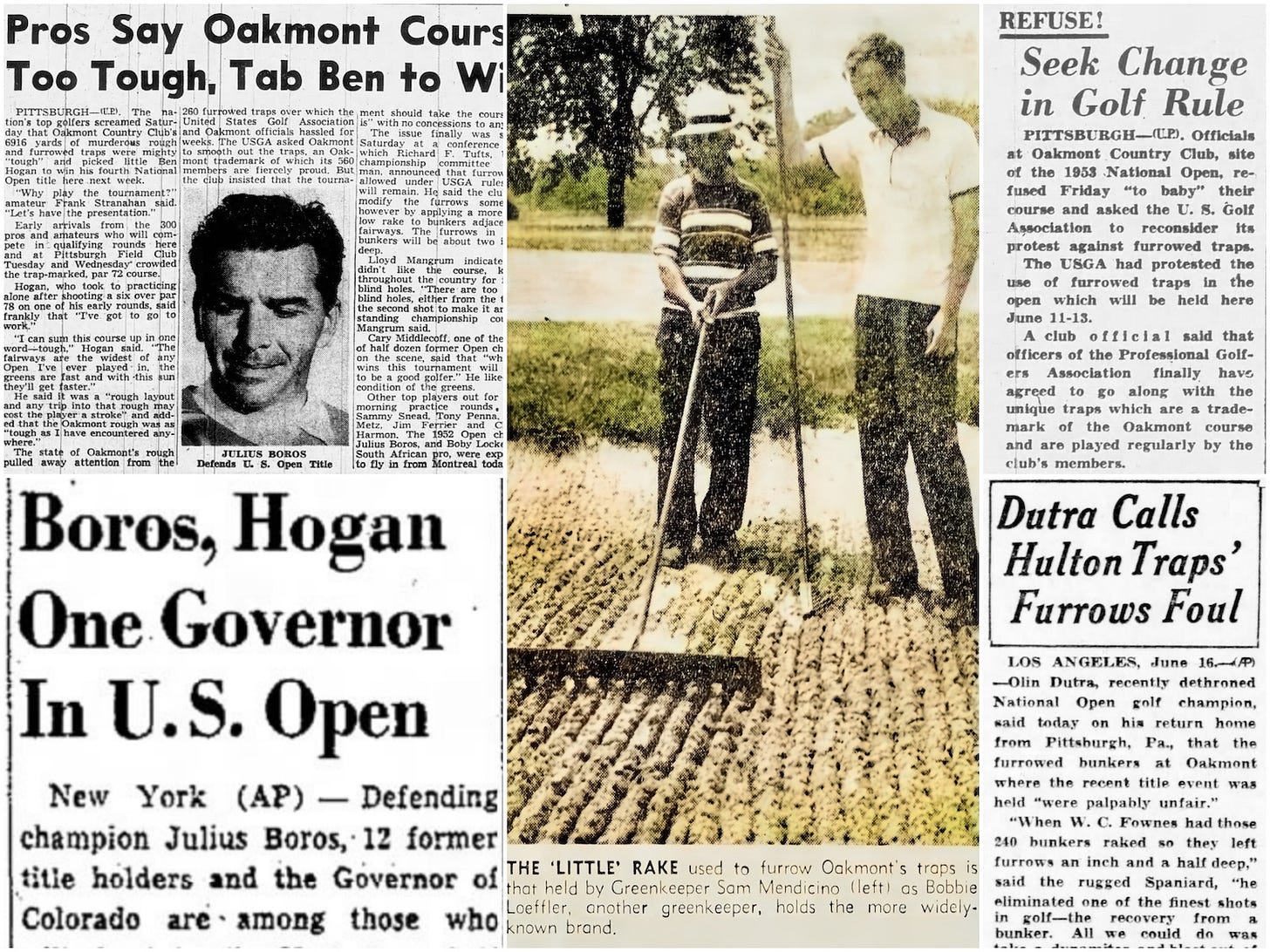

After negotiating with the PGA of America, the USGA and Oakmont agreed to a compromise only after the club’s president returned from a trip the weekend before the National Open. The USGA declared furrows “legal” under the Rules of Golf, which sounded more like an excuse to appease the club since no one questioned the legality, just the contrived nature of the practice. Then-championship committee chair Richard Tufts convinced the club to use a modified 2-inch tine and to only treat the greenside bunkers with furrows.

The compromise was revealed in a UPI wire service story: “A club official said that officers of the Professional Golfers Association finally have agreed to go along with the unique traps which are a trademark of the Oakmont course and are played regularly by the club's members.”

The USGA’s Joe Dey sought to downplay any setup concerns.

“Oakmont’s famous bunkers won’t be furrowed as deeply as they are for day-to-day play,” he told UPI. “Fairway bunkers won’t have any furrows at all. When the Open was there in 1935, it was custom to roll the greens frequently to make them faster. Rolling greens has been abandoned. These greens now are as true as can be found.”

The furrowing remained for 36-hole qualifying where the 23-year-old Arnold Palmer made it through to make his U.S. Open debut (he shot 84-78-MC). Besides Hogan, the field of 300 included Colorado Governor Dan Thornton. The field split their two rounds between Oakmont and Pittsburgh Field Club before the U.S. Open started the next day and with a 36-hole final round set for Saturday.

Detour 1: In case you were trying to do the math: they played qualifying rounds Tuesday and Wednesday, before starting the U.S. Open Thursday, the second round Friday and a 36-hole final day Saturday. That’s six competitive rounds in five days with all but one round at Oakmont.

Detour 2: There were no recovery boots, cryo chambers, physios, or wholly organic farm-to-table player dining.

After qualifying, 40-year-old Hogan complained he was “dead tired” and not on his game prior to the championship. Naturally, he opened Thursday with a tournament-low 67 (−5). Hogan came back in even-par 72 on Friday and took a two-stroke lead over Sam Snead and George Fazio into Saturday’s 36-hole finale. A Hogan-Snead duel developed, with Snead trailing Hogan by one shot with nine holes to go. But Hogan famously made three’s from the 15th hole to the 18h to finish six clear of Snead, who fell apart and posted a final round 76 to Hogan’s 71.

While Hogan went off to Carnoustie and his eventual Open triumph, several players were still hot about Oakmont’s setup even as they turned attention to a PGA Championship boycott (over the perceived flukiness of match play).

“I won't play in the Open again under present conditions,” said two-time U.S. Open runner-up Clayton Heafner, who was known for his temper. “I know four other players, Sam Snead, Lloyd Mangrum, Cary Middlecoff and maybe Jack Burke who won't play either.”

The story noted dissatisfaction due to “hoaxing up of golf courses for the Open” while charging that the USGA “favors” Ben Hogan in the assignment of pairings and starting times in the Open. Middlecoff apparently picked up in the third round in protest against his starting time, while Burke said the purse “money isn't distributed fairly” by the USGA.

Only Heafner kept his word and retired from competitive golf altogether. He passed away seven years later at age 46 following a heart attack.

Burke would play seven more U.S. Opens, Middlecoff 11 additional times (including a win and playoff loss), Mangrum four more, and Snead another 18 times, including two more at Oakmont. Short memories!

Jimmy Demaret finished fourth in the 1953 U.S. Open and summed up the furrowing rake.

“You could have combed North Africa with it and Rommel wouldn’t have got past Casablanca.”

The 1962 U.S. Open

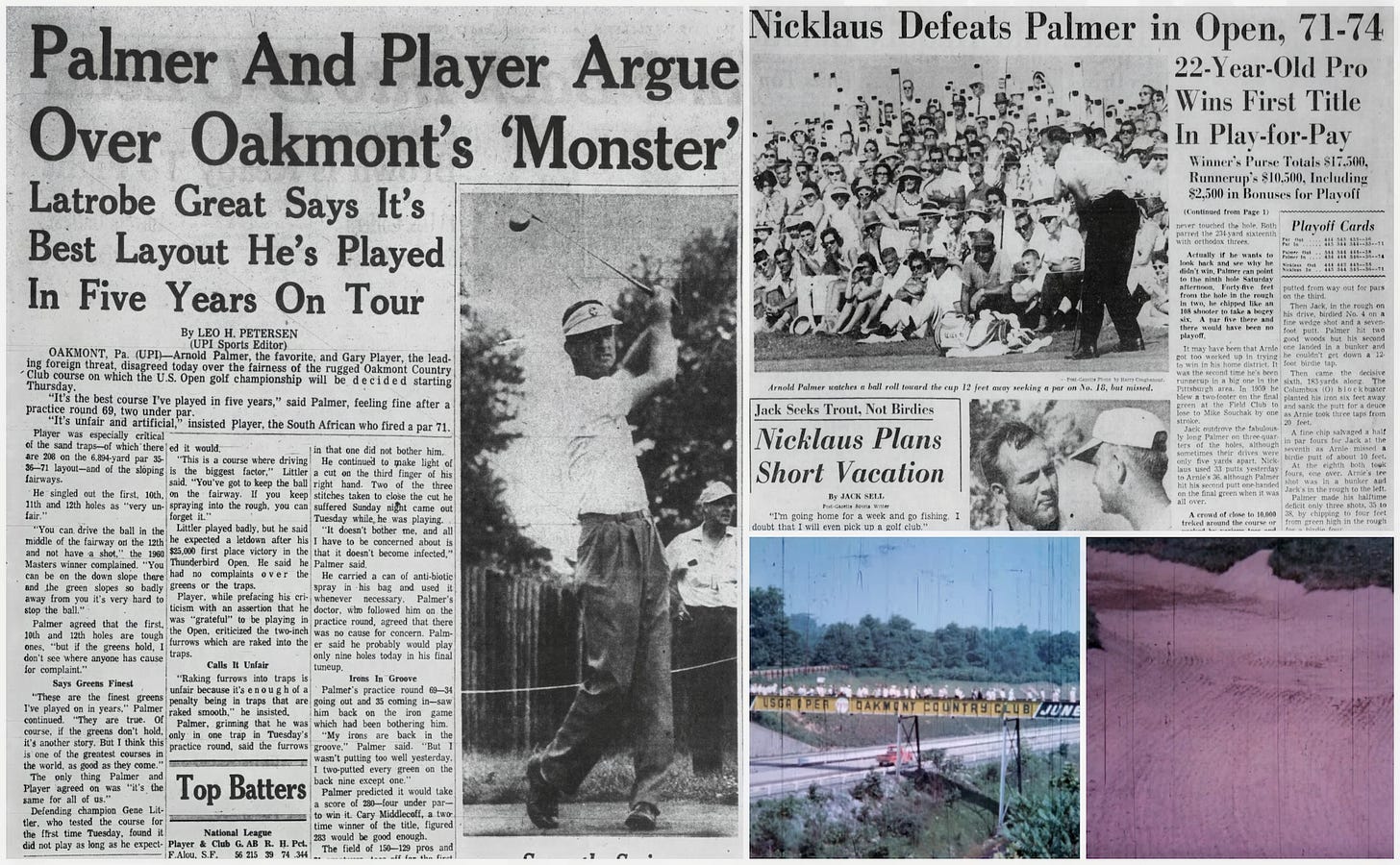

Everything was about Latrobe’s Arnold Palmer attempting to win in front of “Arnie’s Army” and over a course he first played at age 12. But 22-year-old Jack Nicklaus spoiled the party by winning a playoff over Palmer, who three-putted 11 times during a week when Oakmont’s greens weren’t even as fast as anticipated. Nicklaus only three-putted once.

The early week headlines revolved around a cut Palmer sustained on the third finger of his right hand while placing luggage in his car at Latrobe airport. He required three stitches and played the practice rounds with an antibiotic spray to keep the bandaged wound clean.

News accounts focused on this and a tussle—at least in the minds of headline makers—over Palmer and Gary Player’s different Oakmont takes.